SOUTH AFRICAN ASSOCIATION OF CONSULTING ENGINEERS

Submissions re the Preferential Procurement Policy Framework Act 5 of 2000

TO:

The Select Committee on Finance, ParliamentBY: Made on behalf of the South African Association of Consulting Engineers (SAACE)

DATE: Tuesday, 16 September 2003

1. Introduction

Preferential procurement is one of the tools that the state may use to transform the socio-economic landscape in South Africa. Transforming a country where serious inequalities have existed for more than 300 years is, however, not a task for the faint-hearted.

There are various ways in which the state can go about this transformation. The starting point, we suggest, is the preamble to the Constitution, Act 108 of 1996.

It reads that the Constitution was adopted as the supreme law of the Republic so as to improve the quality of life of all citizens and free the potential of each person; and to build a united and democratic South Africa able to take its rightful place as a sovereign state in the family of nations.

These are more than mere laudable goals. Section 1 of the Constitution reads that the Republic of South Africa is founded on values like the achievement of equality and values like non-racialism and non-sexism. In our view it is clear that these Constitutional values will only be achieved by programmes like ‘affirmative action’ and ‘black economic empowerment’ which complies with the basic norms and values embodied in section 217 of the Constitution..

The SAACE has a vision for black economic empowerment that it would like to share with the committee. This vision is in line with the ideals of the RDP. First, however, we have to sketch a very bleak (in fact, pale male) picture of civil engineering in South Africa.

The environment from which SAACE draws its members

The SAACE is defined in its Constitution as a body whose members "are primarily in the business of offering independent technology-based intellectual services in the built, human and natural environment to clients for a fee".

Mr. Peter Silbernagl, Immediate Past President, South African Association of Consulting Engineers presented a paper DEMOGRAPHICS IN CIVIL ENGINEERING: WHAT FUTURE? ,at the SAICE congress in May 2003.

He did an analysis of some of the determinants of the future of civil engineering in South Africa with particular reference to consulting engineering and a preliminary identification of the challenges this analysis presents. A full copy of the paper is attached hereto as Annexure A.

Some salient points form the paper is highlighted hereunder.

2.1 Transformation Charter

The Association adopted a Transformation Charter in 2000 and each mandated principal, i.e. the person representing the member firm, was requested to sign such Transformation Charter and to display it publicly in the offices of that firm. The Association has spoken out against "fronting" by consulting engineering firms and is of the view that fronting is not in the interests of the client, consulting engineers or society.

The Association is also developing an Empowerment Strategy and is negotiating a research contract with the CSIR to undertake a study that will lead to a well-informed and broadly supported strategy. One of the main drivers for this study is the persistent lack of appropriate demographic (race and gender) representation in the engineering fraternity. The industry just does not attract enough new entrants from the Designated Groups (as defined in the Employment Equity Act, Act 55 of 1998). A good start would be to review the trends in and status quo of registrations with the Engineering Council of South Africa (ECSA).

2.2 ECSA registrations

According to the paper, the registration of engineers is undertaken in South Africa by the Engineering Council of South Africa (ECSA), a statutory body in terms of the Engineering Professions Act, Act 46 of 2000. Trends in registration with ECSA could thus be a further indicator of the health of the civil engineering profession (civil engineers – including candidate engineers and technologists – comprise 36,7% of all disciplines registered with ECSA).

Figures from ECSA reveal that, on 1 April 2003, Black (male and female, including Coloured and Asian) professional engineers comprised approximately 2,8% of all registered professional engineers in the civil engineering discipline. The table in figure 13 shows that the intake of candidate engineers (previously engineers-in-training) with ECSA may, on the surface, appear as an improvement (23,8%), but in absolute terms the total number of black engineers-in-training registered with ECSA as on 1 April 2003 was 161 persons, i.e. less than one per local authority in South Africa!

Figure 13 – ECSA registrations 1 April 2003

|

|

Civil Eng. PrEng (%) |

Civil Eng. Eng-in-T (%) |

Civil Eng. PrTech (%) |

Civil Eng. Tech-in-T (%) |

|

Black male & female |

2,8 |

23,8 |

9,4 |

62,1 |

|

White male & female |

97,2 |

76,2 |

90,6 |

37,9 |

|

Total (no.) |

5987 |

676 |

393 |

169 |

An analysis of the ECSA registrations over the past ten years shows that, since 1998, total registrations of professional engineers in the civil engineering disciplines have declined from 6 894 to 5 980, i.e. an average of 183 per year. During that period, the number of Black professional engineers (including African, Coloured and Asian, and Black women) registered with ECSA in the civil engineering discipline increased from 154 (2,2%) to 170 (2,8%) individuals. The number of White women increased from approximately 98 (1,4%) to 107 (1,8%) individuals.

Figure 14 – Professional Engineers as registered with ECSA in the civil engineering discipline

|

|

A further look at the New Registrations as Professional Engineers and Candidate Engineers with ECSA shows alarming reductions in new registrations. Whereas a total of approximately 230 PrEng registrations have been lapsing every year for the past five years, only about 50 new registrations have entered the pool, leading to a nett decline of about 180 PrEng registrations per annum (see figure 15).

Taking a look at the information from a demographic point of view shows that new registrations for both Professional Engineers and Candidate Engineers for both Blacks and females have in fact declined since 1996/97!

2.3 What's happening at the universities?

Horak concluded that the "fall out" rate in civil engineering at universities is approximately 31% from entrant to graduate level. Data obtained from a few universities corroborates the finding by Horak, but also highlights the fact that in order to assess the rate of entrance of new civil engineers, it would be best to analyse the figures of graduates only (see figure 17).

Figure 17 – Graduates vs Intakes (Civil Engineers): Summary from 8 universities

|

|

It should be noted that neither the information for the ECSA registrations, nor the university graduates, deal with citizenship, which could become an issue when formulating strategies with respect to Procurement Policies and Employment Equity Plans! Of significance, though, for ECSA, the Association and SAICE, is the fact that in 2000 white males comprised 62% of all civil engineering graduates at South African universities! (see figure 20).

|

Figure 20 – Civil engineering: Graduates of all universities in 2000 (Data from Stats-SA)

|

Thus even if the percentage of white males graduating in civil engineering were to reduce to 5% within the next five years, it would take at least a further 45 years until the demographic distribution of the SAICE members and the Professional Engineers registered in the civil engineering discipline would match the general demographics in the country. Of course, more drastic measures like early resignation from SAICE or lapsing of registrations (voluntary or otherwise) would speed up this process. Interventions such as quotas at universities have been used before in South Africa! One shudders to think what impact this may have on economic growth and development. In all likelihood, the process would take a very long period.

Of course, the assumption is that there would be matriculants with higher-grade maths and science, and that these matriculants would prefer civil engineering to other choices.

2.4 What about maths and science at school?

Our future civil engineering university graduates and professional civil engineers should come from a pool of school leavers matriculating with higher grade maths and science. An analysis of the matriculants provides a most disturbing picture, as seen in figure 21. It demonstrates the devastating effect of the legacy of not having provided higher grade maths and science teachers in the so-called Black schools in the past. From these figures it appears that the number of Black (African) matriculants passing with higher-grade maths is reducing. Why would the few who matriculate with higher grade maths choose a career in engineering, specifically civil engineering, when there are alternatives such as IT, management consultancy, accounting, business management, medicine and others available to them? Making more bursaries available to these high quality matriculants, on its own, will not solve the problem.

Figure 21 – Percentage of matriculants qualifying with Higher Grade Maths

Of course, all efforts must be made to improve the teaching of maths and science, particularly in the so-called Black schools, and many of our members participate in special maths and science teaching programmes. Tribute must also go to the National Department of Education for the National Strategy for Maths, Science and Technology Education and to the Western Cape Department of Education for its Maths, Science and Technology Strategy, including the launch of the Centre of Science and Technology. Some successes have been reported, but in some areas it is of a very low base, e.g. in 2001 only 28 matriculants passed with higher-grade maths from "DET" schools in the Western Cape.

Many other notable efforts have started elsewhere, including more broad-based approaches such as the one by the Gauteng Department of Transport, which is reported to provide additional maths and science education to 800 scholars.

Necessary as these efforts are, they are not enough to make the profession attractive enough for new entrants to remain in civil engineering.

2.5 The problem the SAACE is faced by

The vast majority of the registered civil engineers are pale male. As was said above, the failure to provide higher-grade maths and science teachers in the so-called Black schools in the past, has left a devastating legacy. It appears that the number of Black (African) matriculants passing with higher-grade maths is reducing. Why would the few who matriculate with higher grade maths choose a career in engineering, specifically civil engineering, when there are alternatives such as IT, management consultancy, accounting, business management, medicine and others available to them?

It is imperative that funds and skills are invested in providing higher grade maths and science teachers in schools all over the country.

The lack of black and female faces in engineering, however, flies in the face of government policy. In the Western Cape, for instance the proposed Preferential Procurement Implementation Plan of the Department of Transport and Public works of the Western Cape sets a totally unrealistic participation target for:

HDI Ownership of at least 40% for all goods and services procured.

Woman / Disabled of at least 20% within 5 years for all goods and services procured. These targets do not relate to reality.

When comparing these targets to the reality of the demographics in engineering, it becomes evident that there is a chasm between theory and reality. SAACE agrees with the government that there are too few Black or women engineers.

But what should SAACE do until there is a bigger field of matriculants with higher grade science and maths to draw from? It is not possible for a pale male to change his gender or his race.

We are now proceeding to discuss the relevant legislation and will then make certain proposals on transforming the demographics of engineering and building the country as a whole. Planning and supervising building is what civil engineers are trained to do.

3. Background to the legislation

Section 217 (1) of the Constitution sets certain standards for any organ of state that contracts for goods or services. The procurement must be done in accordance with a system, which is fair, equitable, transparent, competitive and cost-effective. Subsection (2) allows ("does not prevent") the organs of state to implement a procurement policy providing for:

(a) categories of preference in the allocation of contracts; and

(b) the protection or advancement of persons, or categories of persons, disadvantaged by unfair discrimination.

It is of great significance that national legislation must prescribe a framework within which the policy referred to in subsection (2) must be implemented. The section had read earlier on that the policy referred to in subsection (2) may be implemented. It has been amended to must.

Compare the obligation that national legislation must prescribe a framework within which the procurement policy must be implemented, with the contents of section 2 of the Constitution.

In section 2 it is stated that the Constitution is the supreme law of the Republic; law or conduct inconsistent with it is invalid, and the obligations imposed by it must be fulfilled. It is thus imperative that national legislation prescribes a framework policy for all cases where a policy provides for categories of preference in the allocation of contracts and the protection or advancement of persons (or categories of persons) disadvantaged by unfair discrimination.

In the matter of EX PARTE CHAIRPERSON OF THE CONSTITUTIONAL ASSEMBLY: IN RE CERTIFICATION OF THE CONSTITUTION OF THE REPUBLIC OF SOUTH AFRICA, 1996* 1996 (4) SA 744 (CC) the court held that the provision in the chapter that national legislation should determine a framework for affirmative action policies in respect of procurement was consistent with CP XXI, and was not an encroachment on the legitimate autonomy of the provinces. (Paragraph [285] at 857E.)

In the matter of PRETORIA CITY COUNCIL v WALKER 1998 (2) SA 363 (CC) the court held that a requirement of s 33(1) was that a right could only be limited by a law of general application and, since the respondent's challenge was directed at the conduct of the council, which was clearly not authorised, either expressly or by necessary implication by a law of general application, that s 33(1) was not applicable to the present case. (Paragraph [82] at 396E/F--G, 415G/H--I/J.)

The right which we are referring to in these cases [where a policy provides for categories of preference in the allocation of contracts and the protection or advancement of persons (or categories of persons) disadvantaged by unfair discrimination] is the right to equality.

The basic principle that was established by our Constitution, Act 108 of 1996, is that everyone is equal before the law and has the right to equal protection and benefit of the law. (Section 9(1)). This echoes what was said in the Preamble: ‘every citizen is equally protected by law’.

Section 33 to which the Walker case referred, has been replaced by the current s36, which deals with the limitation of rights. S36 (1) reads that the rights in the Bill of Rights may be limited only in terms of law of general application to the extent that the limitation is reasonable and justifiable in an open and democratic society based on human dignity, equality and freedom.

In line with the reasoning of the court, preferential procurement policies should also be reasonable and justifiable.

4. Constitution and Act: Policy Framework

When one compares this to the obligation in section 217 (3) of the Constitution that national legislation must prescribe a framework within which the policy referred to in subsection (2) must be implemented, then it appears that no policy that does not fall squarely within a law of general application prescribing a framework, may be lawfully implemented.

The phrase in section 217 (2) "does not prevent" organs of state from implementing a procurement policy providing for categories of preference and the protection or advancement of persons, means that the organ of state has a choice whether it wants to implement such a policy. But, when it decides to implement such a policy, it must implement the policy within the framework prescribed by national legislation.

The PREFERENTIAL PROCUREMENT POLICY FRAMEWORK ACT 5 OF 2000 and the Regulations issued in terms of the Act is the law of general application that sets a framework for the implementation of a preferential procurement policy. In terms of section 2(1) of the act an organ of state must determine its preferential procurement policy and implement it within the framework prescribed in the act.

In terms of the definitions clause in section 1(i) of the Act, acceptable tender means "any tender which, in all respects, complies with the specifications and conditions of tender as set out in the tender document". Section 2 (1) (c) also refers to tender(s).

This leads one to infer that the act only refers to those cases where there was a tender document with the specifications and conditions of tender. This means that the Act does not regulate all instances where the state implements a procurement policy providing for categories of preference in the allocation of contracts and the protection or advancement of persons, or categories of persons, disadvantaged by unfair discrimination (as set out in section 217(3)). This is despite the fact that section 217(3) instructs that national legislation must prescribe a framework within which the policy referred to in subsection (2) must be implemented.

At a glance it seems that the act is seriously flawed in that it only provides a framework for cases where an invitation to tender have been put out. There is no framework that applies when professionals do work on a tariff-based system when tenders are not called for. The Act therefore does not fully fulfil its obligations set by s 217 of the Constitution.

The Preferential Procurement Regulations R725 of 10 August 2001 defines "Contract" to mean "the agreement that results from the acceptance of a tender by and organ of state".

"Tender" means "a written offer or bid in a prescribed or stipulated form in response to an invitation by an organ of state for the provision of services or goods".

In terms of Regulations 2(3) of the Regulations an organ of state may deviate from the framework contemplated in section 2 of the act in respect of a pre-determined tariff based professional appointments.

However, the moment an organ of state implements a procurement policy providing for categories of preference in the allocation of contracts; and the protection or advancement of persons (or categories of persons, disadvantaged by unfair discrimination) the organ of state must implement the policy within a framework that must be prescribed by national legislation.

This means that the moment there is any policy to advance previously disadvantaged persons, the policy framework prescribed by national legislation must be adhered to. It is doubtful whether regulation 2(3) of the regulations can lawfully allow an organ of state to deviate from the framework contemplated in section 2 of the act in respect of a pre-determined tariff based professional appointments.

The fact that there may be deviations from the prescribed framework has already lead to certain Procurement Policies of organs of state not only deviating, from but being contrary to the principles of the Constitution and the PPPF Act. Examples e.g. from the Eastern Cape Provincial Administration and the Western Cape Provincial Administration can be provided to the Committee, if so required.

5. The disadvantages of requiring professionals to tender

The attention of the committee is drawn to the Green Paper on Public Sector Procurement Reform in South Africa. In paragraph 4.5 the appointment of consultants is discussed from pages 101 to 107 and it inter alia stated that:

" The calling for open tenders under all circumstances, even for routine

assignments, is neither in an organ of State's, nor the consultant's interests.

Apart from an organ of State's costs in preparing and adjudicating such tenders

and the consultant's costs in submitting tenders, such practices will favour

the established large consultancies who have greater capacity to absorb the

costs. Medium and small companies and, in particular, emerging consultants,

are at a distinct disadvantage. Elaborate and complex adjudication systems are

required for the satisfactory adjudication of tenders for consulting services.

A major problem with competitive tendering relates to the definition of the

scope of services to be performed. Consultants cannot price their services if

these are ill defined. In research and development, policy formulation, human

resource development, community-based developments and the like, the scope of services can seldom be well defined prior to the commencement of the project or commission.

For engineering and construction projects, life cycle costs are most critical

and are largely dependent on design quality. Any potential saving in the

design fee would form only a minuscule portion of the life cost of the project

and should not be allowed to jeopardise the best value for money option on the

project as a whole.

Likewise, the costs of policy research are trivial relative to the impacts of

policy decisions on the nation. The selection of consultants on the basis of

price alone may well lead to unsatisfactory, or even disastrous outcomes which

could, in all likelihood, have been avoided at insignificantly greater overall

cost.

International experience regarding competitive tendering for professional

services has been mixed.

In the United Kingdom, surveys have indicated that where competitive fees (lowest price) was the criteria foraward, clients on engineering and construction contracts got less value for money, as consultants were reluctant to consider alternatives, produced simpler designs, resisted client changes, spent less resources on education and training etc. Current thinking is to opt for the awarding of contracts on the basis of a quality / price mechanism, in terms of which price, depending upon the nature of the services required, accounts for from 15% to 50% of the points allocated.

The World Bank has no requirement for competitive tendering for consulting

services and recommends that selection be based primarily on quality. Price

forms part of the selection process only where projects are of a routine

nature, and proposals are judged to lead to comparable outputs.

The principle factors which the World Bank suggests that should be used when

deciding upon appointments are:

assignment; and

The specific needs of emerging consultants owned and controlled by previously

disadvantaged individuals must be taken into account. Although this group of

consultants may demonstrate competency, they are likely to lack experience

which can only be obtained through the granting of appointments.

Current practices which are being pursued to facilitate the participation of

emerging consultants and to reward consultants who have been proactive in

developing previously disadvantaged individuals within their companies or

developing capacity in emerging consultancies, include insisting that all work

be performed in association with such enterprises, accelerated roster systems,

joint venture requirements, and the scoring of adjudication points.

Information provided by established firms in support of human resource

development and social responsibility programmes is extremely difficult to

verify and is seldom called for. Furthermore, such criteria frequently favour

the large firms who, for various reasons relating to scale of operation, have

more scope and opportunity to meet such criteria, particularly as their

contributions are seldom measured in terms of their turnovers. Thus, although

such systems may achieve their objectives in providing work for emerging

consultants and rewarding pro-active established consultants, it is vulnerable

to window-dressing and fronting and generally favours the larger consultancies,

Many organs of State have established panels of consultants who have the

necessary experience and expertise to provide routine services e.g. auditing,

design, contract administration, legal advice, etc. Certain appointments made

to firms on these panels have resulted in strong relationships which have

endured for long periods and a number of these panels have not incorporated any new panellists from the time that they were originally constituted.

Organs of State, other than those functioning at national level, often require

consultants to maintain local offices within their areas of jurisdiction. In

many instances such offices do not, in fact, perform the work using their own

resources.

Instead they pass it through to associated offices in other centres. This

practice is very difficult to monitor and the consequence is that appointments

to consultants with local offices do not necessarily lead to local economic

development.

Given the efficiency and speed of current modes of information transfer, the

desirability of consultants being required to maintain local offices, which may

be mere facades, is questionable. It may, in fact, be submitted that the

requirement for maintaining a local office is a form of local preference, which

works against free trade within the country and is, therefore, in conflict with

the constitution.

Under certain circumstances, particularly where work of a highly specialised

nature is required, it may be advantageous to approach a particular firm, or

individual consultant, rather than to conduct a selection process. Such

appointments would, normally, be desirable where the particular consultant has

been closely involved in work similar to that required, or has expertise not

widely available. Appointments of this nature are unavoidably open to abuse

and criteria and policy in respect of sole service providers needs to be

formulated.

There is a need in regard to construction projects to have available standard

sets of interlocking professional appointment documents which not only govern

the conditions of the appointment but also set out, as far as possible, the

services to be performed by consultants and the relationships which such

consultants have with construction contractors and other consultants. This is

particularly necessary to enable "non-traditional" consultants e.g. training

managers, mentors, project facilitators, contract compliance monitors, etc. to

be appointed to ensure that development objectives are met and to describe the services required of consultants where non-traditional contract delivery

options or new forms of contracts are utilised on projects.

ii. Proposals

1. Tariff appointments (fixed scales of fees or prescribed rates)

data base, using a method that over a period of time will afford all

those on the list an opportunity of participation, to submit proposals

and make the appointment on the basis of the quality offered;

assignments; or

that those on the panel have equitable / balanced work loads commensurate with their abilities and capabilities

2. Competitive tendering :

capabilities, capacity and experience, appropriate for the required

service which is to be performed, selected from a comprehensive data

base in such a manner that over a period of time all those on the data

base will have an opportunity to tender, or

mechanism and reject any tenderer who does not meet a minimum quality

threshold.

reference / scope of the work can be adequately defined.

tenders should be documented and submitted for review to the Procurement

Compliance Office.

application to join such panels on an ongoing basis.

adjudication team score submissions, a similar result would be obtained.

individuals whose turnovers are within predetermined limits, should be

afforded accelerated work opportunities. Accelerated work opportunities for

such firms should be achieved by means of one or more of the following:

human resource specifications to ensure that the target group

consultants are engaged either as sub-consultants for distinct portions

of the work or as joint venture partners.

appointments to control the end product.

consultants maintaining offices within a specific geographic area should, in general, be discontinued. Only where it can be demonstrated that clear advantages would accrue to the organs of State by the use of local consultants should the selection be confined to them.

Procurement Compliance Office regarding all appointments of consultants.

Particulars of the scope and nature of assignments, the terms of appointment

and remuneration, the estimated fee amounts and the departments, or sections requesting the appointments should be furnished".

SAACE agrees in essence with these views expressed in the Green Paper. A distinction should remain regarding the appointment of Consultants on the following methods:

It is in the interest of all stakeholders that the possibility of making tariff appointments without going through the procurement process should not be removed. The appropriate way to deal with this aspect as far as preferential procurement is concerned is to have two appropriate frameworks:

6. Vision

In terms of Regulation 17 of the regulations, the tendering conditions may stipulate that specific goals, as stipulated in section 2(10) (d) (ii) of the Act, be attained. The act states in this section that the specific goals may include implementing the programmes of the Reconstruction and Development Programme as published in Government Gazette 16085 dated 23 November 1994. A number of activities may be regarded as a contribution towards achieving the goals of the RDP. Some of the relevant ones are:

Our vision is

All of this accords with the Preamble to the Constitution that states that: ‘we therefore, through our freely elected representatives, adopt this Constitution as the supreme law of the Republic so as to-

7. Conclusion

SAACE is aware of questions being raised by certain roleplayers whether the system on fixed tariff appointments should not be terminated. This would result in tenders being the only applicable system. For the reasons fully set out in the Green Paper quoted above, SAACE is opposed to the possible scraping of the fixed tariff appointment system.

The correct way to deal with this issue is NOT to do away with fixed tariff appointments, but to also develop a framework for fixed tariff appointments.

Both the Preferential Procurement Policy Framework Act, 5 of 2000, and the Regulations issued in terms of the act, refer in the definition of "contract" and "acceptable tender" and is applicable only to those cases where there was a tender document with the specifications and conditions of tender. This means that the prescribed framework does not regulate all instances where the state or organs of state implements a procurement policy providing for categories of preference in the allocation of contracts and the protection or advancement of persons, or categories of persons, disadvantaged by unfair discrimination (as set out in section 217(3) of the Constitution).

This is despite the fact that section 217(3) instructs that national legislation must prescribe a framework within which the policy referred to in subsection (2) must be implemented.

At a glance it seems that the both the Act and the Regulations are seriously flawed in that it only provides a framework for cases where invitation to tender have been put out. There is no framework that applies when professionals do work on a tariff-based system. It can thus be argued that both the Act and the Regulations issued in terms of the Act does not fulfil its obligations set by s 217 of the Constitution.

8. Recommendation

Submitted on behalf of SAACE and prepared by

ATTORNEY LEN DEKKER ADV. MARIKA VAN DER WALT

ANNEXURE A

DEMOGRAPHICS IN CIVIL ENGINEERING: WHAT FUTURE?

An analysis of some of the determinants of the future of civil engineering in South Africa with particular reference to consulting engineering and a preliminary identification of the challenges this analysis presents

Peter Silbernagl

Immediate Past President, South African Association of Consulting Engineers

Director, Liebenberg & Stander

P O Box 4733 Tel: 021 421 2430

Cape Town Fax: 021 421 1985

8000 E-mail: [email protected]

INTRODUCTION

At a time when the South African Institution of Civil Engineering celebrates its centenary year, it is appropriate to take stock and to reflect on the status quo of and prognosis for civil engineering.

The South African Association of Consulting Engineers (SAACE) celebrated its 50th anniversary last year, and so it also seems appropriate to reflect on the status quo of and prognosis for civil engineering particularly within the field of consulting engineering in South Africa.

The word "consultant" is described as "a person providing professional advice, etc., esp. for a fee" – Collins English Dictionary. The SAACE is defined in its Constitution as a body whose members "are primarily in the business of offering independent technology-based intellectual services in the built, human and natural environment to clients for a fee".

A CLOSER LOOK AT CIVIL ENGINEERS

Background

The South African Institution of Civil Engineering has several membership grades, with the categories of Member and Fellow forming the heart of the Institution (53% of the qualified members, i.e. excluding students).

Figure 1 – SAICE membership (April 2003)

|

|

No. |

% |

|

Members & senior members |

2 844 |

37.1 |

|

Fellows |

357 |

4.7 |

|

Technologists |

254 |

3.3 |

|

Graduates > 5 years |

873 |

11.4 |

|

Graduates < 5 years |

377 |

4.9 |

|

Associate members |

579 |

7.6 |

|

Retired (all grades) |

451 |

5.9 |

|

Other (incl. ICE) |

324 |

4.2 |

|

Students (Technikon & University) |

1 609 |

21.0 |

|

TOTAL |

7 668 |

100 |

(with acknowledgement to Ms Memory Scheepers, SAICE)

Worrying, though, is that the average age of the Members and Fellows is just over 51 and 58 years respectively. The concerns about this relatively high average have been highlighted in papers by Lawless (2002) and Horak (2002). Concerns include: Will there be enough new entrants coming through to replace the Mr Average who will be retired within the next 13 years?

Figure 2 – Age distribution of SAICE members

|

|

(from Horak)

A MUCH CLOSER LOOK AT CONSULTING ENGINEERING

Membership of the South African Association of Consulting Engineers is by firm (not individual). Last year, in its Jubilee year, membership of the Association breached the 400 firm ceiling, and now stands at over 430 firms as members, which in turn employ some 11 000 members of staff (professional, technical and support). Firm sizes vary from one person practices to a few firms with staff complements exceeding 500 people, with one or two firms around the 1 000-employee mark. A typical distribution of the firm sizes is given below:

Figure 3 – Typical distribution of firm sizes

Thus approximately 90% of all members of the Association qualify for SMME status in terms of the National Small Business Act, No. 102 of 1996.

The predominant number of firms are small firms, i.e. employing fewer than 20 people, and these make up more than 75% of all firms. On the other hand, the largest 12% of firms employ approximately 68% of all staff.

Figure 4 – Firm size vs. number of employees

|

|

Client spread

An analysis of the distribution of clients as evident from the twice-annual Management Information Survey conducted by SAACE of its members, shows that the private sector was steadily gaining in market share at the cost of the public sector, but this trend seems to be reversed, as given in the graph below.

Figure 5 – Client distribution

The geographic spread of the fee income given in figure 6 shows Gauteng dominating. An unresolved uncertainty in this survey is whether projects, say, in the Eastern Cape done for National Public Works are classified as Gauteng projects or Eastern Cape projects. Significant, though, is the 21% of fee income generated from outside South Africa. The Association believes that this percentage is under-reported due to various company structures and country-specific legal and tax requirements. It is estimated that a foreign exchange inflow of approximately R900 million is earned annually by members from this work.

Figure 6 – Provincial market share as at Dec 2002 and % change on Dec 2001

|

|

A further analysis of the markets (see figure 7) indicates that civil engineering continues to dominate.

Figure 7 – Market share by major disciplines

|

|

International links: Africa and beyond

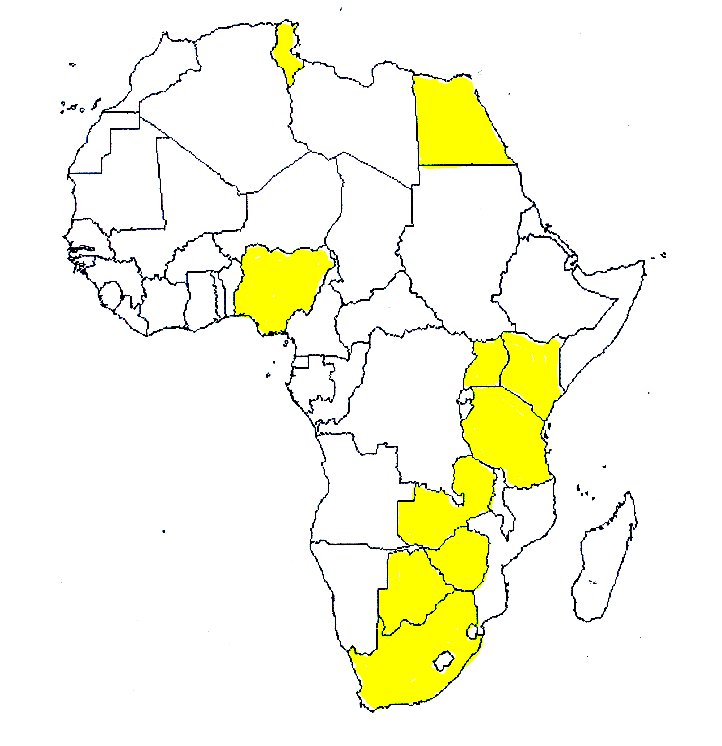

Formal international contact is maintained with FIDIC (International Federation of Consulting Engineers), the international umbrella body seated in Switzerland that represents consulting engineers world-wide. Of the 67 countries represented, the Association is the 10th largest. A subset of FIDIC is the Group of African Member Associations (GAMA), where 10 African countries, including the Association, are currently active participants. Previously GAMA had a membership of approximately 15 countries from Africa of the potential 53 African countries, including the Indian Ocean islands, but this has recently dwindled to 10 active countries, due to the uncertainty of the status of some countries which have not paid their subscriptions to FIDIC, or which have withdrawn when the depreciation of their currencies made membership unaffordable. No other Association in Africa has a full-time secretariat, let alone an Executive Director of the calibre of Graham Pirie PrEng. The Association's membership fees to FIDIC are currently R200 000 per annum.

Figure 8 – GAMA members: South Africa, Botswana, Zimbabwe, Zambia, Tanzania, Kenya

Uganda, Nigeria, Egypt, Tunisia

GAMA members, south of Sahara

|

|

No. Staff |

% of Staff |

|

Botswana |

515 |

4.2 |

|

Kenya |

36 |

0.3 |

|

Nigeria |

1067 |

8.8 |

|

South Africa |

9430 |

77.5 |

|

Tanzania |

262 |

2.2 |

|

Uganda |

253 |

2.1 |

|

Zambia |

198 |

1.6 |

|

Zimbabwe |

410 |

3.4 |

|

TOTAL |

12 171 |

100.0 |

|

Egypt ) FIDIC members, data not included (also members of FCIC - Tunisia ) Federation of Consulting Engineers in Islamic Countries) |

||

Notably, Namibia is no longer a member of FIDIC.

AN EVEN CLOSER LOOK AT CONSULTING ENGINEERS

Employment trends

When one takes a much closer look at the consulting engineering profession, a very different picture emerges. Figure 9 shows the employment trend over the past five years, and also tracks the fee income as gleaned from the Management Information Survey. A slightly coarser evaluation of employment trends, as evident from the annual returns for renewing membership, indicates a similar pattern and, disconcertingly so, also over a longer period. Since 1998 the total number of people employed by members has reduced from approximately 12 600 to 10 800 although the total number of members has increased from 365 to 430 firms, and no big firms have left the Association. Should the members not have earned the fees from work done outside South Africa, the employment levels would probably have dropped by a further 20%.

Figure 9 – Employment vs real value of fee income

|

|

When one compares the general trend of the most direct indicator of construction activity, gross fixed capital formation, there is no surprise (see figures 10 and 11). It does show though, both from employment levels and from macro-economic analysis, that the opportunities for consulting engineers have reduced by approximately 50% in 25 years – clearly, a "profession in crisis", as it has been described elsewhere.

Figure 10 – Gross fixed capital formation as percentage of GDP

Figure 11 – Employment by consulting engineers

|

|

Not surprisingly, consulting engineers have become more innovative in their offering to clients, and now move up and down the project "food chain" (such as project identification, initiation, funding, and operation and maintenance), or have gone into quite different dimensions on projects (such as community education, debtor management, asset management, etc.).

Salaries of Civil Engineers

The P-E Corporate Services salary survey is conducted annually, covering a vast number of employer bodies in South Africa which employ a total of approximately 1,5 million people. A subset of this dataset deals with civil engineers, electrical engineers, etc. and also with consulting engineering firms and their staff. Approximately 80 consulting engineering firms participate in the survey, and since many of these are the larger firms, it is estimated that approximately 80% of all staff employed by member firms are covered by the survey. The survey for September 2001 showed that the gross remuneration package paid to civil engineers working for consulting engineers is approximately 40% lower than those employed elsewhere. This analysis was confirmed in a letter by Martin Westcott, Managing Director of P-E Corporate Services, to Graham Pirie, Executive Director of the Association: "At present the comparative ratio between consulting engineers and total market remuneration ranges between 1,2 and 1,4 for the 25 positions that are described in both surveys, i.e. the national data is on average between 1,2 and 1,4 times the consulting engineers' data. Graduate engineers, technicians/technical assistants show the highest differential. The ratio is 1,42 in the case of graduate engineers."

In the most recent survey (see figure 12) this ratio improved somewhat, but it still shows a differential of almost 40% for graduate engineers.

Figure 12 – Civil engineers' remuneration packages

|

|

TRANSFORMATION AND THE NUMBERS GAME

Transformation Charter

The Association adopted a Transformation Charter in 2000 and each mandated principal, i.e. the person representing the member firm, was requested to sign such Transformation Charter and to display it publicly in the offices of that firm. The Association has spoken out against "fronting" by consulting engineering firms and is of the view that fronting is not in the interests of the client, consulting engineers or society.

The Association is also developing an Empowerment Strategy and is negotiating a research contract with the CSIR to undertake a study that will lead to a well-informed and broadly supported strategy. One of the main drivers for this study is the persistent lack of appropriate demographic (race and gender) representation in the engineering fraternity. The industry just does not attract enough new entrants from the Designated Groups (as defined in the Employment Equity Act, Act 55 of 1998). A good start would be to review the trends in and status quo of registrations with the Engineering Council of South Africa (ECSA).

ECSA registrations

Registration of engineers is undertaken in South Africa by the Engineering Council of South Africa (ECSA), a statutory body re-formed in terms of the Engineering Professions Act, Act 46 of 2000. Trends in registration with ECSA could thus be a further indicator of the health of the civil engineering profession (civil engineers – including candidate engineers and technologists – comprise 36,7% of all disciplines registered with ECSA).

Figures from ECSA reveal that, at 1 April 2003, Black (male and female, including Coloured and Asian) professional engineers comprise approximately 2,8% of all registered professional engineers in the civil engineering discipline. The table in figure 13 shows that the intake of candidate engineers (previously engineers-in-training) with ECSA may, on the surface, appear as an improvement (23,8%), but in absolute terms the total number of black engineers-in-training registered with ECSA as at 1 April 2003 was 161 persons, i.e. less than one per local authority in South Africa!

Figure 13 – ECSA registrations 1 April 2003

|

|

Civil Eng. PrEng (%) |

Civil Eng. Eng-in-T (%) |

Civil Eng. PrTech (%) |

Civil Eng. Tech-in-T (%) |

|

Black male & female |

2,8 |

23,8 |

9,4 |

62,1 |

|

White male & female |

97,2 |

76,2 |

90,6 |

37,9 |

|

Total (no.) |

5987 |

676 |

393 |

169 |

An analysis of the ECSA registrations over the past ten years shows that, since 1998, total registrations of professional engineers in the civil engineering disciplines have declined from 6 894 to 5 980, i.e. an average of 183 per year. During that period, the number of Black professional engineers (including African, Coloured and Asian, and Black women) registered with ECSA in the civil engineering discipline increased from 154 (2,2%) to 170 (2,8%) individuals. The number of White women increased from approximately 98 (1,4%) to 107 (1,8%) individuals.

Figure 14 – Professional Engineers as registered with ECSA in the civil engineering discipline

|

|

A further look at the New Registrations as Professional Engineers and Candidate Engineers with ECSA shows alarming reductions in new registrations. Whereas a total of approximately 230 PrEng registrations have been lapsing every year for the past five years, only about 50 new registrations have entered the pool, leading to a nett decline of about 180 PrEng registrations per annum (see figure 15).

Figure 15 – New registrations: Professional Engineers (Civil)

|

|

When one delves a bit deeper, one discovers that the pending change in registration procedures probably caused a flurry of new PrEng registrations in 1998, but it probably does not explain the continued low level of registrations thereafter. Taking a look at the information from a demographic point of view shows that new registrations for both Professional Engineers and Candidate Engineers for both Blacks and females have in fact declined since 1996/97! (See figures 15 and 16.)

Figure 16 – New registrations: Candidate Engineers (Civil)

|

|

Interesting to note is that the median ages at registration as a Candidate Engineer and as a Professional Engineer are 25 and 34 years respectively.

What's happening at the universities?

Horak concluded that the "fall out" rate in civil engineering at universities is approximately 31% from entrant to graduate level. Data obtained from a few universities corroborates the finding by Horak, but also highlights the fact that in order to assess the rate of entrance of new civil engineers, it would be best to analyse the figures of graduates only (see figure 17).

Figure 17 – Graduates vs Intakes (Civil Engineers): Summary from 8 universities

|

|

Taking the two Western Cape universities that offer courses in civil engineering, for example, two different pictures emerge (see figures 18 and 19).

Figure 18 – Civil engineering graduates at the University of Cape Town

|

|

Figure 19 – Civil engineering graduates at the University of Stellenbosch

|

|

It should be noted that neither the information for the ECSA registrations, nor the university graduates, deal with citizenship, which could become an issue when formulating strategies with respect to Procurement Policies and Employment Equity Plans! Of significance, though, for ECSA, the Association and SAICE, is the fact that in 2000 white males comprised 62% of all civil engineering graduates at South African universities! (see figure 20).

|

Figure 20 – Civil engineering: Graduates of all universities in 2000 (Data from Stats-SA)

|

Thus even if the percentage of white males graduating in civil engineering were to reduce to 5% within the next five years, it would take at least a further 45 years until the demographic distribution of the SAICE members and the Professional Engineers registered in the civil engineering discipline would match the general demographics in the country. Of course, more drastic measures like early resignation from SAICE or lapsing of registrations (voluntary or otherwise) would speed up this process. Interventions such as quotas at universities have been used before in South Africa! One shudders to think what impact this may have on economic growth and development. In all likelihood, the process would take longer than 60 years, probably closer to 100 years.

Of course, the assumption is that there would be matriculants with higher grade maths and science, and that these matriculants would prefer civil engineering to other choices.

What about maths and science at school?

Our future civil engineering university graduates and professional civil engineers should come from a pool of school leavers matriculating with higher grade maths and science. An analysis of the matriculants provides a most disturbing picture, as seen in figure 21. It demonstrates the devastating effect of the legacy of not having provided higher grade maths and science teachers in the so-called Black schools in the past. From these figures it appears that the number of Black (African) matriculants passing with higher grade maths is reducing. Why would the few who matriculate with higher grade maths choose a career in engineering, specifically civil engineering, when there are alternatives such as IT, management consultancy, accounting, business management, medicine and others available to them? Making more bursaries available to these high quality matriculants, on its own, will not solve the problem.

Figure 21 – Percentage of matriculants qualifying with Higher Grade Maths

Of course, all efforts must be made to improve the teaching of maths and science, particularly in the so-called Black schools, and many of our members participate in special maths and science teaching programmes. Tribute must also go to the National Department of Education for the National Strategy for Maths, Science and Technology Education and to the Western Cape Department of Education for its Maths, Science and Technology Strategy, including the launch of the Centre of Science and Technology. Some successes have been reported, but in some areas it is of a very low base, e.g. in 2001 only 28 matriculants passed with higher grade maths from "DET" schools in the Western Cape.

Many other notable efforts have started elsewhere, including more broad-based approaches such as the one by the Gauteng Department of Transport, which is reported to provide additional maths and science education to 800 scholars.

Necessary as these efforts are, they are not enough to make the profession attractive enough for new entrants to remain in civil engineering.

RESPONSE BY CONSULTING ENGINEERS

Employment trends

The employment statistics as shown by the Management Information Survey (MIS) of December 2002 indicate a steady and improving number of black directors, associates, etc. with the members of the Association (see figures 22 and 23), thus indicating inordinately good progress by members of the Association – in relative terms – but still dismally poor and unacceptable in absolute terms. Not all Partners/Directors and Associates are necessarily professionally registered, but the results do show the intent.

Figure 22 – Employment breakdown: Workforce analysis, Jun – Dec 2002

|

|

Figure 23 – SAACE Management Information Survey, Dec 2002

|

|

Partner/ Director |

Associate |

PrEng/Tech |

|

Black |

12% |

12% |

5% |

|

White |

88% |

88% |

95% |

|

Total (no.) |

1156 |

612 |

521 |

The MIS also shows that with respect to recruitment, approximately 98% of all responses indicate problems with the recruitment of PDI engineers due to lack of candidates (see figure 24).

Figure 24 – Recruitment problems

|

|

Education and training efforts by members

Members of the Association contribute annually in excess of R35 million for education and training of their staff and students over and above the levies such as the Skills Development Levy. In 2001 approximately 700 bursaries went to black students. These efforts are in addition to the endeavours by the School of Consulting Engineers of SAACE. The School, which was founded as an outcome of the Vision 2000, facilitates courses and seminars provided by others, but which are relevant to consulting engineering.

IMPLICATIONS

Clearly there is a tension between the supply (of HDI PrEngs, new HDI entrants) and the demand (of Procurement Policies, of the Employment Equity Act). From the analysis above it is clear that the demographic representivity will not change substantially in the short term. On the other hand, pressure exists on client representatives to demonstrate immediate and substantial progress towards transformation objectives.

It therefore seems reasonable to assume that the civil engineering industry, including consulting engineering firms, will respond in order to remain relevant and competitive, by changing ownership structures and representation on their boards of directors. These new owners and directors would only in rarer cases be Professional Engineers registered with ECSA in the civil engineering discipline. Many would probably be Black businessmen and women, whose careers have probably not grown out of civil engineering initially. How this change in ownership and executive management will impact on the culture and ethics now prevalent in civil engineering, especially consulting engineering, only time will tell.

The most crucial key to the future lies in the Procurement Policies of clients. Will these policies measure transformation objectives by taking into account the professional registration of owners, executive management and staff? The future of civil engineering lies in the answer to that question.

THE CHALLENGE

The challenge for the leaders and elected representatives in civil engineering is thus to attract new entrants that would enable a correction of the demographic profile. For this objective to be achieved, the following aspects should be included in a strategy for the profession:

Improve the risk/reward equation

- Improve opportunities and salaries for civil engineers

- Reduce professional risks (e.g.. limit liability in time and in quantum)

- Reduce commercial risk (e.g. by overcoming boom/bust economic cycle in civil engineering)

- Identify work which should be done by professional engineers and consider compulsory registration

Promote better image (but only after the above items have been attended to successfully)

- This includes more interaction at schools, universities and on client education

- Support medium to large firms and engage these more as fast-track nurturing grounds, for on-the-job training and mentoring

Improve fee regimes

- Without money, none of the above is possible, and new entrants will be drawn elsewhere (Generation X).

Many of these steps have been started and this bodes well for the future.

SO WHAT DOES THE FUTURE HOLD? ARE THERE ANY OPPORTUNITIES?

The following are some of the factors that improve the prognosis for civil engineering in the future:

Government's commitment to economic growth, especially the statements made by the Minister of Finance, Min. Manuel in his Budget speeches, both last year and this year, and the intentions of government as reflected in the Medium Term Expenditure Framework, especially with respect to increased investment in infrastructure.

Figure 25 – Macroeconomic projections

|

|

Actual/Estimate |

MTEF |

||||

|

|

2000/01 |

2001/02 |

2002/03 |

2003/04 |

2004/05 |

2005/06 |

|

GDP Real % change |

3.1 |

2.7 |

3.2 |

3.4 |

3.8 |

4.0 |

|

GFCF Real % change |

0.8 |

3.6 |

6.3 |

5.8 |

6.4 |

6.9 |

GFCF = Gross fixed Capital Formation, one of the best indicators for construction activity.

Source: Treasury

SAACE Management Information Survey July – Dec 2002

Implementation of NEPAD in Africa. Estimates abound, but vast investment is needed to build the infrastructure in Africa – some estimates are quoted at US$ 70 billion per annum.

Increased foreign direct investment (FDI) by South Africa in Africa. It has been reported at a UN Conference on Trade & Development that South Africa has become the most important source of FDI in Africa, averaging US$ 1 billion per year since 1994. In the SADC region, the FDI provided by South Africa exceeds that for the USA and the UK combined (Financial Mail, 7 Feb 2003).

The formation of the Construction Industry Development Board, formed in terms of the Construction Industry Development Board Act, Act 38 of 2000, which heralds a new era for the construction industry in South Africa. The mandate of the board is to develop the construction industry and there is a sense of earnestness to rebuild an industry that was almost destroyed.

Improved fee scales and time basis rates as published on 28 February 2003 in the Government Gazette by ECSA. A step in the right direction, but much more attention is still needed to the risk/reward and value equations.

The potential therefore exists for a substantial improvement in the general climate for civil engineers, and especially for consulting engineers. These opportunities exist both within South Africa and beyond.

CONCLUSION

The future of civil engineering lies in the hands of the key stakeholders which includes client bodies.

There should be no doubt that the civil engineering fraternity (which includes brothers and sisters) has demonstrated remarkable resilience and ingenuity in weathering the storms over the past few decades. It has also clearly signalled that they are more than ready, able and willing to rise to the challenges. It is now time for the civil engineer to stand up and be counted, to contribute meaningfully to reconstruction and development, to make NEPAD succeed, to fast-track Black economic empowerment and to help with economic upliftment, which should reduce poverty and the impact of HIV/AIDS in the profession, but only if all stakeholders take up their responsibilities.

The question is: Will clients, as stakeholders, help make this partnership work?

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I am indebted to my colleagues Jane Edwards and Zaheer Ortell for their support and assistance in researching and assembling this paper. Grateful acknowledgements for provision of information go to Johan Pienaar of ECSA, Johan van Schalkwyk and Jean Stanford of the South African Association of Consulting Engineers, Prof Emile Horak of Pretoria University and Martin Westcott of P-E Corporate Services.

REFERENCES

Department of Education. National Strategy for Mathematics, Science and Technology Education in General and Further Education and Training. (June 2001).

ECSA (Engineering Council of South Africa). Number of intakes vs. no. of graduates for 8 universities (individually) 1980 – 1988. (2003).

ECSA. Registration information.

FIDIC. FIDIC Info 03. International Federation of Consulting Engineers. (2003).

Gaum, A (Western Cape Education Minister). Launch – WCED's Maths, Science and Technology Strategy. 18 February 2003.

Honey, P. SA tops Africa's investors' list. Financial Mail p25 (7 February 2003).

Horak, E. Where is the next generation? Published in Sabita Digest pp 36-47, South African Bitumen Association. (March 2002).

Jawitz J and Case J. Exploring the Reasons South African Students Give for Studying Engineering. Faculty of Engineering, University of Cape Town. (1998).

Lawless, A. The Internet for improved service levels. Paper presented at IMESA Conference. (October 2002).

P-E Corporate Services SA (Pty) Ltd. South African Association of Consulting Engineers: An Evaluation of Current Remuneration Practices and Market Rates. (November 2002).

Paterson, A and Visser M. The Matric Examinations: Tools for Analysing Performance. Published in Indicator SA Vol 19 No 1. pp 63-70. (2001).

Silbernagl, H P. Consulting Engineers: A National Asset: Where to now? Paper presented at IMESA Conference. (October 2002).

Statistics SA. Information on all students classed by university, including enrolments, graduations. Race, gender classifying for 2000, 2001.

University of Cape Town. Engineering registration information 1988 – 2002 categorised separately by race and gender. (2003).

University of Pretoria. Engineering registration information 2001 and 2002, categorised by race and gender. (2003).

Westcott, M J R. Letter from P-E Corporate Services to SAACE. (4 June 2002).